When The Loop at Chaska opens in Summer 2024 it will set a new benchmark for fun and accessible public golf. The project was the brainchild of non-profit Barrier Free Golf, which also contributed US$1 million in funding.

Read Bradley Klein’s report for the USGA Green Section Record here ≫

Golf Digest: 11 municipal courses that are getting the love they deserve ≫

Golf.com: The Loop is focusing on access just as much as design ≫

The City of Chaska, Minnesota, is synonymous with elite tournament golf. Since it was founded in 1962, Hazeltine National, a private club on the north side of town, has hosted four US Opens (two for men and two for women), the Ryder Cup, the US Amateur, the Women’s PGA, and numerous other national events. Hazeltine will host a second Ryder Cup in 2028.

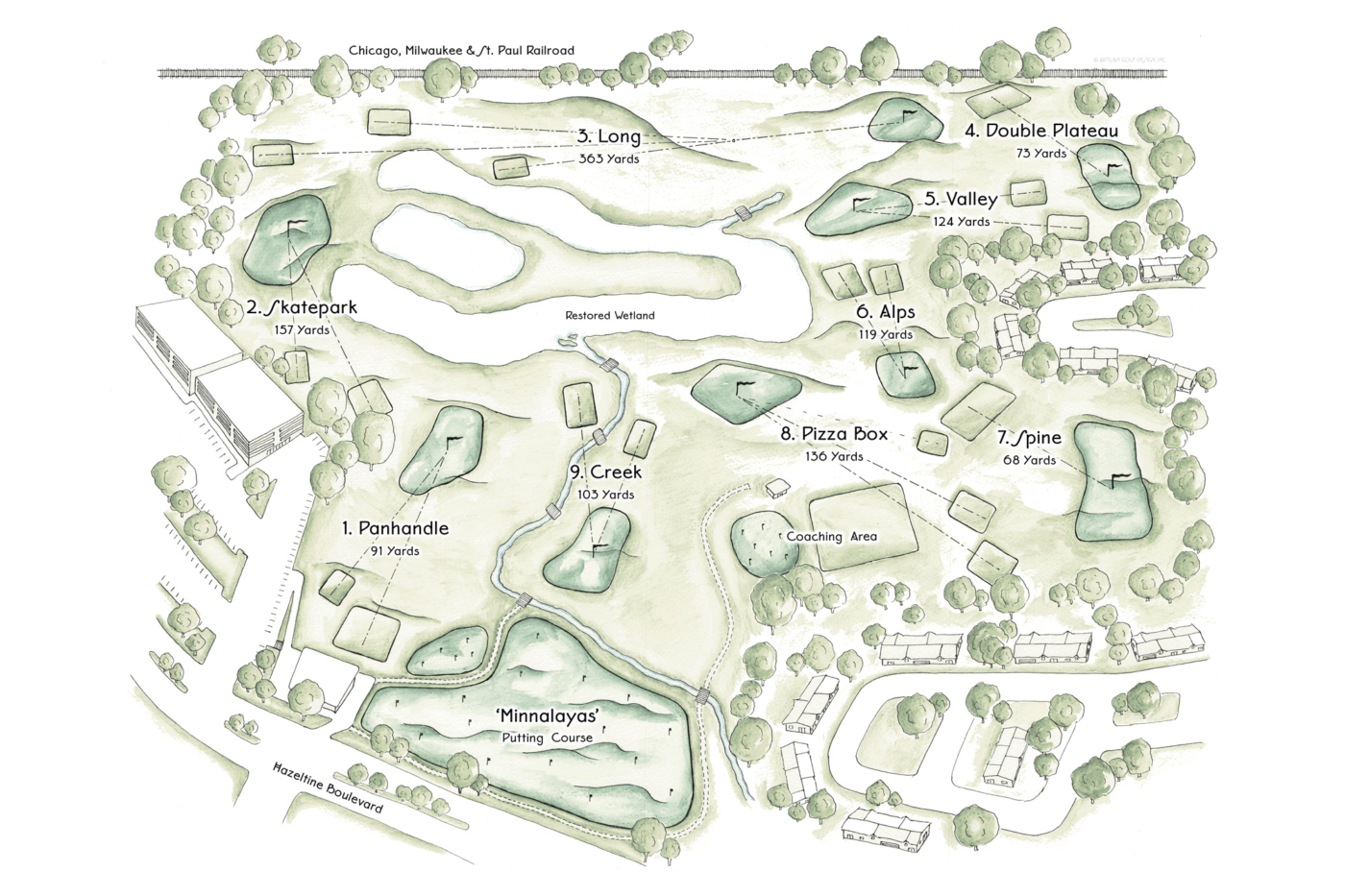

Now, thanks to a partnership with Barrier Free Golf, city leaders are nurturing the grass roots of the game. A three-year effort to reimagine and rebuild the Chaska Par 30 golf course—which will be rebranded The Loop at Chaska—is creating a national showcase for entry level golf which is fun, accessible and sustainable.

In Chaska, Barrier Free Golf took the lead on project fundraising, the development of the creative brief, and in helping the project partners allocate charitable donations and city funds where they would have the greatest impact. Golf course architect Benjamin Warren was hired to anchor the design team. World class shapers Jim Craig, Brett Hochstein and Jonathan Reisetter built the greens. Minnesota-based Dan Beiganek—who was the site lead for contractor Mid-America Golf—completed a Herculean twelve months of lake construction and shaping work, and also contributed two greens.

Project highlights include:

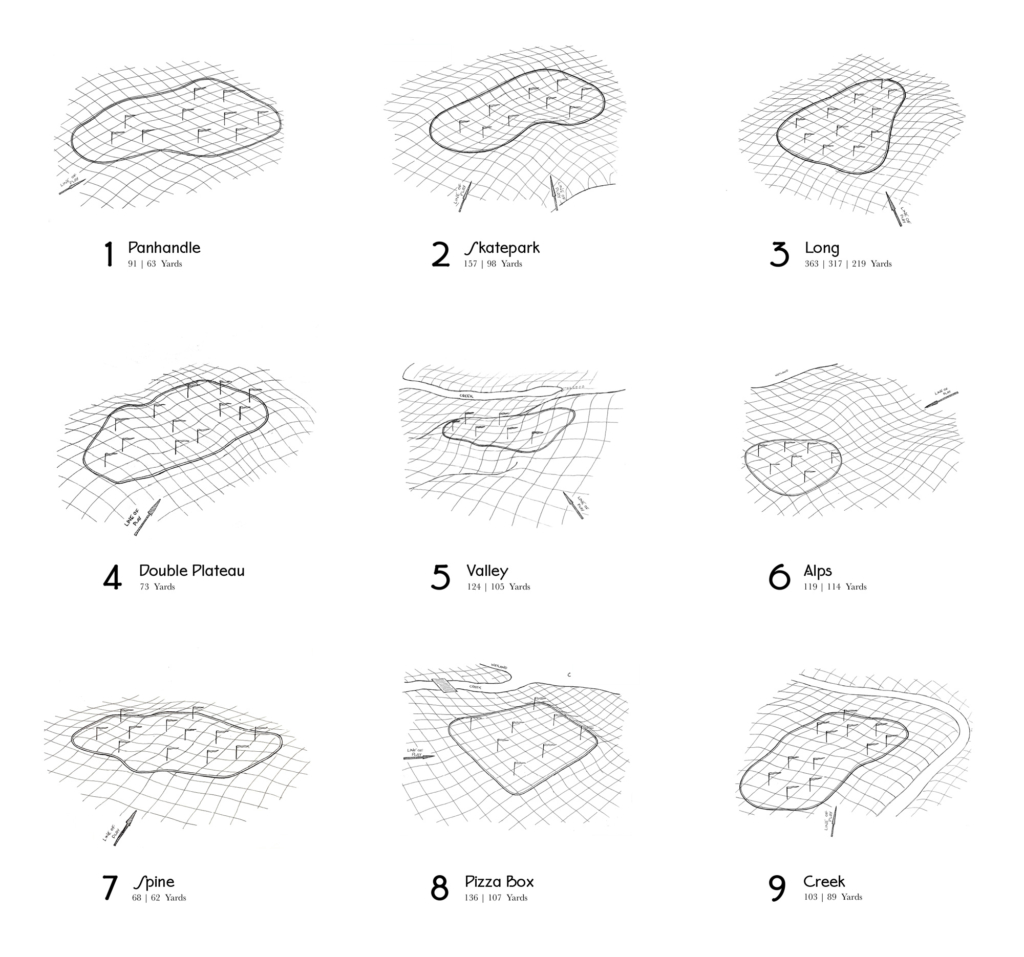

- New 1,234-yard short course with holes ranging from 70 to 370 yards

- New ‘Minnalayas’ putting course

- New clubhouse

- Occasional coaching area (for new junior and adaptive golfers; course reduced to 8-hole loop)

- Restored five-acre wetland

- Irrigation source transitioned from groundwater to captured stormwater

- No maintained rough

- Fun greens!

- No bunkers!

But why dedicate so much time, talent and investment to reimagining a humble muni short course?

The barriers to learning golf are real. The game is hard. Equipment and coaching can be expensive. Dress codes are intimidating. Practice facilities can be sterile and unfriendly.

Barrier Free Golf is committed to changing this, one course at a time.

Introducing a beginner to the game at even a mundane eighteen hole golf course is the equivalent of teaching someone to ski by sending them down a triple black diamond run. New golfers who have the opportunity to cut their teeth at a fun short course are the fortunate few. The combination of playing golf in a natural setting and seeing one’s ball react to ground contours cannot be replicated at a driving range or in a simulator.

Introducing a beginner to the game at even a mundane eighteen hole golf course is the equivalent of teaching someone to ski by sending them down a triple black diamond run.

When Barrier Free Golf founder Tim Andersen approached the City of Chaska with a vision to transform Chaska Par 30 into a showcase project for fun and accessible golf, he was determined that the course should also welcome golfers with disabilities.

In Benjamin’s response to the project RFP, and then again during an interview with the selection panel, he made it clear that Artisan Golf Design had a lot to learn about adaptive golf. He was certain, however, that one tried and tested entry point to the game would be perfect for new adaptive players.

In many communities in Scotland—Benjamin’s homeland—complete beginners can enjoy the feeling of trundling a golf ball over some cool contours towards a hole on a public putting course. The ‘Himalayas’ in St Andrews, is the oldest and most famous of these facilities. It was natural that Artisan Golf Design’s proposal should be anchored by a 30,000 square foot putting course in a highly visible location on Hazeltine Boulevard.

For the design of the short course itself, Benjamin asked the panel to imagine a scaled out nine-hole version of a Himalayas putting green with acres of tightly mown fairway grass and no maintained rough. He believed that golfers of all ages and abilities should be able to play the golf course by bunting shots across the ground. This was music to the ears of Barrier Free Golf.

Having grown up on the links of Scotland, Benjamin is a ‘ground game’ specialist. When the average golfer is assessing their shot options from 90 to 140 yards they instinctively select a lofted club and hit the ball through the air, even if the ground to be covered is wide open ’fairway’. To the amusement of his playing partners, when faced with this type of shot, Benjamin will often reach for a six-iron, skip his ball across the turf, and feed it towards the hole using the ground contours. This type of shot is similar to the full shots of slow swing speed golfers such as seniors, juniors and adaptive players, who typically struggle to loft the ball into the air.

As detailed design work got underway in Chaska the adaptive golf community was supportive. A roundtable event hosted by Barrier Free Golf brought together blind, amputee, autistic and paraplegic golfers, and experts from national and international associations such as the US Adaptive Golf Alliance, and the European Disabled Golf Association, to review the golf course plans and provide input. This group confirmed that the most challenging categories of adaptive golfer to design for would be the seated players—those who play using solorider or paragolfer units—and certain lower-leg amputee golfers. It was confirmed that a golf course which would be fully navigable for seated golfers would be suitable for the wider adaptive golf community.

But can courses which are welcoming for players with disabilities really be fun for all golfers? In early discussions, the adaptive golf community made it clear that the majority of fairway and green contours need not be softened on their account. A golf course which was not enjoyable for able-bodied golfers would have been deemed a failure. Solving this riddle became the central challenge for the golf design team.

Short courses have never been more popular. Indeed, since the 2012 opening of Coore & Crenshaw’s Preserve at Bandon Dunes, each of the new generation of golf resorts has added a small format course to its offering. The developers of these resorts—Bandon Dunes, Sand Valley, Barnbougle, and Cabot Links, to name but a few—recognize the economic value of these facilities. Guests who travel to stay in remote locations for two or three days, with the goal of playing golf from sunrise to sunset, are smitten by these one-hour aperitif/digestif golf experiences, which can be enjoyed before or after their main course of eighteen or thirty-six holes. Resort-based short courses are wildly popular, and due to their small turf footprint, are typically, in a per-acre comparison, the most profitable tracts of golf at these resorts.

And cities are not being left behind. Success stories like Winter Park Nine, Goat Hill Park, Canal Shores, and now The Loop at Chaska, have shown that city leaders and leaseholders are willing to invest in upgrades to compact golf properties. Indeed, most cities already operate a short course which could be reimagined to appeal to the widest possible set of golfers.

One significant challenge in Chaska would be that ‘ground game’ approach shots require dry soils. The dirt around Lake Hazeltine is relatively poor and the design team would have to get creative if the golf course was ever to play fast and firm.

To tackle this problem Artisan Golf Design enlisted the help of veteran golf course design and build expert Tom Mead, a former superintendent at Crystal Downs in Michigan, and a former associate of Tom Doak’s Renaissance Golf Design.

Mead applied sustainable drainage principles and determined that the first step to remediate the poor soils would be to revert the site hydrology to pre-golf conditions.

Back in 1972 Robert Trent Jones Sr.’s team excavated a wet meadow in the centre of the property to create an artificial lake. Their end goal was to perch four of the nine greens right next to this water hazard.

Tom’s plan to restore the wetland would help to lower the water table in the center of the property by almost two feet, thus presenting moisture in the soil profile with a route to move towards the new resting water level of the wetland. The intended shaping of the golf course would also speed up the surface grades to let rainwater sheet across the property more effectively. The final part of the plan called for the installation of ‘sand slit’ drainage in key playing areas.

It is important to note that the ability to drive a paragolfer or solorider onto a green surface is integral to seated play. Thus, during and after significant rain events these vehicles can damage soil structure and turfgrass and their use may be temporarily suspended, while walking play might still be allowed. USGA guidelines for adaptive play recommend that each course publishes a written policy stating their thresholds for rain events and the suspension and resumption of seated play. In all cases, the superintendent has the final say.

Another key project goal was to enlarge an existing stormwater retention pond so that the maintenance team would be able to meet the irrigation needs of the golf course with captured rainwater, in all but the most severe drought conditions. Reinstating the surrounding wetland helps to clean stormwater and golf course run-off as it moves towards the irrigation lake. The city’s engineering firm led this aspect of the design work.

Early in the design process it became clear that re-routing golf holes would be necessary. The team did not take this decision lightly. Once you start moving golf holes the knock-on effects can be significant. In Chaska we ended up re-routing the entire golf course.

The project team also decided to move the clubhouse to a prominent location on the intersection of Hazeltine Boulevard and Hundertmark Road, allowing us to locate the putting course on the most visible part of the property.

Back in 1972, RTJ lead architect Roger Rulewich routed the original Chaska Par 30 through farm fields. During the subsequent fifty years those farm fields had been replaced by a townhome development to the east, and an office complex to the west. Rulewich’s counter-clockwise routing meant that the prevalent ‘miss shots’ of right handed golfers were now, with regularity, leaving the golf property and endangering neighbouring houses, offices and people.

The decision to reverse the routing meant that the most common miss shots would now veer towards the center of the property, instead of the property line.

With the re-routing approved, irrigation designers Don Mahaffey and Ian Williams of Green Irrigation Solutions specced a super-minimal system. The majority of the golf holes have only single row irrigation, and the total head count on the golf course was kept to 130. For comparison, on many full-size courses a single golf hole can require more heads.

For low-cost muni golf, ease-of-maintenance is critical. The client team agreed to one significant and unconventional design decision: The Loop at Chaska would have no bunkers.

For a solo greenkeeper, maintaining bunkers to a high standard is a thankless and never-ending task. Bunkers also create headaches for the adaptive golf community—especially seated and amputee golfers. Soloriders and paragolfers can navigate hilly terrain, but bunker lips and soft sand can stop them in their tracks. Fortunately the Chaska property has engaging natural contours and our team was confident that we could create memorable golf holes without relying on bunkers to create strategy and visual interest.

As the shaping team started to build greens and surrounds it had on-site support from adaptive golfers Mark Sarkisian—who contracted polio during childhood—and Tanelle Bolt—who sustained a spinal chord injury from an accident in her 20s. Mark and Tanelle stress-tested the severity of the contours, and went out of their way to educate the golf design team about life with disabilities, and the challenges of both navigating golf course features, and playing golf from a seated position.

It’s important to note that simply removing bunkers from a golf course to make it more accessible would have unintended consequences. With no bunkers, the contours in greens, approaches and fairways take on added significance. A ground-up redesign is essential.

Putting surfaces are the most important feature of a golf course, and Barrier Free Golf’s creative brief was crystal clear: The Loop at Chaska must have cool greens.

Putting surfaces are the most important feature of a golf course, and Barrier Free Golf’s creative brief was crystal clear: The Loop at Chaska must have cool greens.

With the knowledge that adaptive golfers would drive mobility devices onto the putting surfaces, ensuring ease-of-maintenance was a top priority. To handle this unconventional traffic load, large putting surfaces would be essential to help spread wear and tear. Sustainable golf design expert Tom Mead and turfgrass and sustainability expert Professor Brian Horgan of Michigan State University, recommended that we seed the greens with ‘007’ bentgrass and target a green speed [stimp reading] of 8.5 to 9.5, which interestingly, was the average speed of Hazeltine National’s greens in 1977, as recorded during a USGA study of national tournament venues. To ensure that our greens would be fun at slower speeds we decided to build the type of bold internal contours which had been commonplace during the golden age of golf course design in America—the 1920s—but which have been eliminated from most modern golf courses in the pursuit of green speeds of 12 to 13 on the stimp, and the need to balance those speeds with playability.

So, can a golf course which is built on heavy soils in the midwest really achieve the fast and firm conditions which will create a fun experience for the target customer groups? If city leaders and the most vocal groups of golfers demand lush fairways which are a uniform green color, the answer will be no.

The temptation at all golf courses, especially when a new irrigation system has been installed at a price tag reaching hundreds of thousands of dollars—typically millions of dollars for an eighteen hole golf course—is to overuse that system. At The Loop at Chaska the maintenance team must receive high level support in its mission to keep the ground conditions as dry as possible. When the goal is to encourage ground game golf, an irrigation system must be treated as insurance for extreme drought conditions, rather than as a ‘set it and forget it’ luxury. Using modern soil moisture sensing technology it is easy to determine when turfgrass needs water to maintain its health and stress tolerance, versus simply throwing out water to maintain a lush green aesthetic. The ‘low mow’ bluegrass specced for the fairway areas at Chaska, if kept lean and mean, will allow running shots to skip across the playing surface. When is comes to the putting green surfaces, the same holds true. Rather than firing the heads on an automatic program when small areas of the greens and surrounds start drying out, the maintenance team can connect hoses to ‘quick couplers’ at the greens and hand-water only the areas which need moisture.

Zooming out, the timing of the Chaska project is quite remarkable.

The announcement that a US Adaptive Open—the first USGA-sanctioned national championship for golfers with physical, visual and intellectual impairments—will take place in Pinehurst in July 2022, means that elite golfers with disabilities will finally have the opportunity to showcase their incredible skills on the national stage. The International Golf Federation is also working hard to have adaptive golf included in the Paralympics. With the establishment of the World Ranking for Golfers with Disabilities, this seems to be well on track.

Barrier Free Golf’s mission is to create opportunities for absolutely anyone, regardless of physical or financial means, to try the game. Our experience in Chaska indicates that a golf course which is welcoming to beginner adaptive golfers need not look all that different to a ‘traditional’ golf course. One thing is certain, any new golfer who is fortunate enough to learn the game at The Loop—and who gets bitten by the bug—will be well prepared to graduate to playing golf at longer and more challenging facilities. But will the big courses be as fun??

Project Credits

Design

- Golf course architect: Benjamin Warren, Artisan Golf Design

- Green design & shaping: Jim Craig, Brett Hochstein, Jonathan Reisetter, Dan Beiganek

- Adaptive golf design consultants: Mark Sarkisian, Tanelle Bolt

- Sustainable design consultant: Tom Mead

- Irrigation design: Ian Williams and Don Mahaffey, Green Irrigation Solutions

- Agronomic consultants: Tom Mead, Prof. Brian Horgan

- Lake and stormwater design: Stantec Engineering

Construction

- General contractor: Mid-America Golf & Landscape

- Project management: Larry Barefield and Casey Hames, Mid-America Golf

- Site manager: Dan Beiganek

- Golf course shaping and lake construction: Dan Beiganek, Chad Whitten

- Irrigation installation: Mid-America Golf

- Drainage and finishing: Mid-America Golf (Rodolfo!)

- Grow-in: Mark Moers, City of Chaska

Leadership

- Barrier Free Golf: Tim Andersen, Susan Neuville, Eric Snyder, David Mooty

- City of Chaska: Matt Podhradsky, John Kellin, Mark Moers, Brian Jung

Adaptive Golf Experts

Barrier Free Golf roundtable participants, March 2021:

- Aaron Holm (double above knee amputee)

- Tanelle Bolt (spinal cord injury)

- Bill Davis (B2 blind)

- Mark Sarkisian (polio)

- Jay Hannon (autism)

- Marcus Williams (spinal cord injury)

- Caroline Mohr (above knee amputee)

- Bob Thibodeau, US Adaptive Golf Alliance

- Mark Taylor, European Disabled Golf Association